One of the most amusing reviews I have seen for War and Peace reads something like: I’m not sure whether I’m awarding five stars to the book or myself for finishing it. Having spent the past six weeks listening to Frederick Davidson narrate War and Peace, I feel as if I should have a certificate somewhere—or at the very least an achievement stating that not only did I finish the book, but both epilogues. Or, I could just write a blog post about it—which many, many other people have done, probably driven by the same urge; a need to say, “I have read it. I have finished one of our greatest works of literature.”

So. Did I enjoy it? Or do I just want to brag about the fact I have read it? The former, definitely. I have no plans to order a t-shirt or register with some secret society. The reason for this post, like all the posts I write about what I’ve been reading, is to share a book I very much enjoyed.

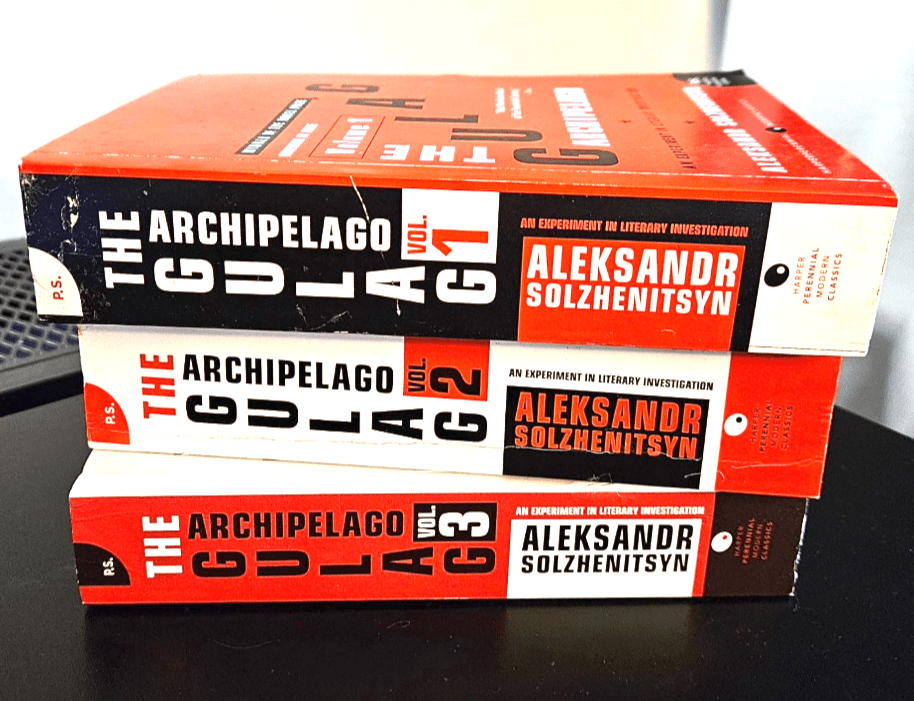

I came to War and Peace a little sideways. I haven’t always wanted to read it, but it was on a list of definite maybes. I even tried once before, about fifteen years ago—shortly after having read (skimmed) Anna Karenina. (I tried, Oprah. I really did.) The impetus to try again came from discovering that the Audible edition’s narrator was Frederick Davidson. I had recently spent 76 hours in the company of Mr. Davidson listening to The Gulag Archipelago (Alexander Solzhenitsyn) for my cultural anthropology class.

I had not only become accustomed to his voice and inflection but felt they would be perfectly suited to Tolstoy’s classic. Also: one credit for nearly 62 hours of audio? What a bargain!

I also felt that after listening to Solzhenitsyn’s epic work, I might be better prepared for another bout of long-form Russian literature. So, as soon as I finished the semester, I loaded War and Peace onto my phone, donned my noise-canceling headphones, and started my mower. (I have a lot of lawn. Like, a lot. While mowing, I listened to Robert McCammon’s Swan Song a few summers ago. 54 hours took me only a couple of weeks.)

My visit to 19th-century Russia became so absorbing that I was soon walking the neighborhood daily to get in another hour. I completed three jigsaw puzzles and my house got very clean.

What I loved most about War and Peace is difficult to separate from an overwhelming sense that all of it was worthwhile. Still, I’ll pick out a few of my favorite aspects, starting with Pierre Kirillitch Bezuhov.

I’m a sucker for the awkward outsider, but it was Pierre’s journey of self-discovery throughout the book that really captured me. He gets some of the best quotes, too:

“They say sufferings are misfortunes, but if I was asked whether I would stay as I was before I was taken prisoner, Or go through it all again, I would say, “For God’s sake, let me be a prisoner again. For me, when our lives are knocked off course, we imagine everything in them is lost. But it is only the start of something new and good. As long as there is life, there is happiness. There is a great deal. A great deal still to come.”

This says so much about what Pierre endured as a character. For almost the whole book he lets other people define his happiness only to discover that he is most happy when he gives up his wealth—and when whatever he has left is taken from him. After the war, he is able to choose what he wants back and it is those decisions, made for himself, that finally bring happiness into his life. That, and his marriage, finally, to a woman he loves.

After finishing the audiobook, I read the brief biographical notes at the front of the Barnes & Noble print edition and saw much of Tolstoy reflected in Pierre, especially in the above quote.

Natasha (Countess Natalya Ilynishna Rostov) also finds herself in times of deepest suffering. Although I’m not sure she ever fully sheds her grief, I felt we saw the most true version of her in the first epilogue. If not a radiant happiness, then a deep contentment with her place.

Prince Andrey Nikolayevitch Bolkonsky gets another of the book’s best quotes:

The whole world is now for me divided into two halves: one half is she, and there all is joy, hope, light: the other half is everything where she is not, and there is all gloom and darkness….”

And this conversation (between Andrey and Pierre) is one of the most wrenching in the book because (spoiler) they both love the same woman.

Natasha’s brother, Nikolay Illytch Rostov appealed as a younger man, but the older he got, the more rigid he became. He needed to grow up and he became an admirable man, but I missed the younger, more carefree Nikolay—his personality—in the epilogue. Then again, he is a perfect example of what war does to a man and one of my favorite scenes in the book is early Nikolay at war.

He enlists to fight Napoleon in Austria, and his first action is facing an enemy charge. His horse is shot from beneath him, and stunned and wounded, he is unable to draw a weapon. He merely stands there, watching the enemy approaching, bayonets pointing at him. His thoughts are what make the scene. He’s like: surely, they can’t mean to harm me? I’m nobody.

The scene felt so true for a young, unprepared soldier, and for Nikolay as a person. And, honestly, I was a bit surprised that he re-enlisted. But he needed the money, and more importantly, something to do. Being a soldier, or having a purpose, eventually defined Nikolay in a way that speaks to the effects of war on the human psyche.

I feel Nikolay had a lot of the younger Tolstoy in him as well. In fact, having served himself, it is not hard to imagine Tolstoy’s message here as anything but intentional—which can be said for most of the book. Which brings me to another of my favorite aspects: the messaging.

War and Peace may be a little slow to start (mostly because there are a lot of people with a lot of names to get used to) but it’s actually quite an easy and engaging read. The characters and their lives are interesting and I quickly became invested in each of their stories. But it was when Tolstoy broke the fourth wall, mentioning his own thoughts (using first person to do so) that I really became absorbed.

As a writer, I am always fascinated by the thought process of other writers and so I loved having Tolstoy outline many of his thought processes right there on the page. Especially during any scene concerning Napoleon’s advance into Russia. Even more especially, connected to the Battle of Austerlitz.

I wondered (briefly) why we don’t all do this? Or at least add two hefty epilogues, one to make absolutely certain of the future of every character and another to explain why we wrote the book and then expound on our theories of related themes.

And that brings me to another of my favorite aspects: the second epilogue. Both epilogues are amazing. The first, because it has chapters and, as stated above, leaves no doubt regarding what everyone gets up to seven years after Napoleon’s occupation of Moscow.

That second epilogue, though. Two years ago, I’d have given it up as unreadable. But, luckily for me, I decided to go back to college two years ago and have so far taken courses on philosophy and cultural anthropology, both of which prepared me for Tolstoy’s take on how history is recorded and a discussion of free will. What I really got out of the second epilogue, though, was why he wrote the book. Tolstoy was a man with big thoughts and little stories weren’t going to allow him to put a lot of them together in the same place, and then stretch and reshape them. With the second epilogue, I gained a better understanding of Natasha’s and Nikolay’s development a little better. Even Pierre’s journey to some extent.

Did I enjoy the sections on war or peace more? Both, equally, I think. They felt like mirror images of story-telling in some ways, and both were important to the development of all the characters. Not so much dark and light as events that changed the course of every life. Tolstoy’s commentary on Napoleon throughout is entertaining, thought-provoking, and quite the inside view of the Russian side of Napoleon’s invasion and how it affected the trajectory of politics and society.

War and Peace is a remarkable book and I’m glad I have read it—but also happy I waited until a point in my life where I had the knowledge and background to truly understand and appreciate it. I could imagine reading it again. I have already leafed through my print copy to write this post, picking out quotes and rereading chapters.

I am also inspired to try Anna Karenina again—this time on audio. But probably not this year. I have at least six more weeks of lawn mowing in the immediate future, but I also have a stack of audiobooks I’ve been saving up for the summer. Shorter books with lighter themes. Still, as I am sure I have made clear, I enjoyed the challenge and can only recommend Tolstoy’s masterpiece to anyone with the time and patience to invest.

Featured Image Credit: Creator: Mitch Jenkins/Kaia Zak | Credit: BBC 2015

Interestingly, in my case I can’t fathom keeping it all straight on an audiobook! However, I read it back in the 70s, and I had several false starts until I found a translation that was readable. Like you, I found it was worth the effort for its own sake, not for bragging rights. In fact, believe it or not, I feel a bit shy about admitting to having read it in a group who likely did not. Nice post.

I’m watching the BBC mini series now and I’m glad I read the book first. There’s so much more to the story than what they show.